How can we unravel the paradox and liberate access to genetic resources for the purposes of conservation and research?

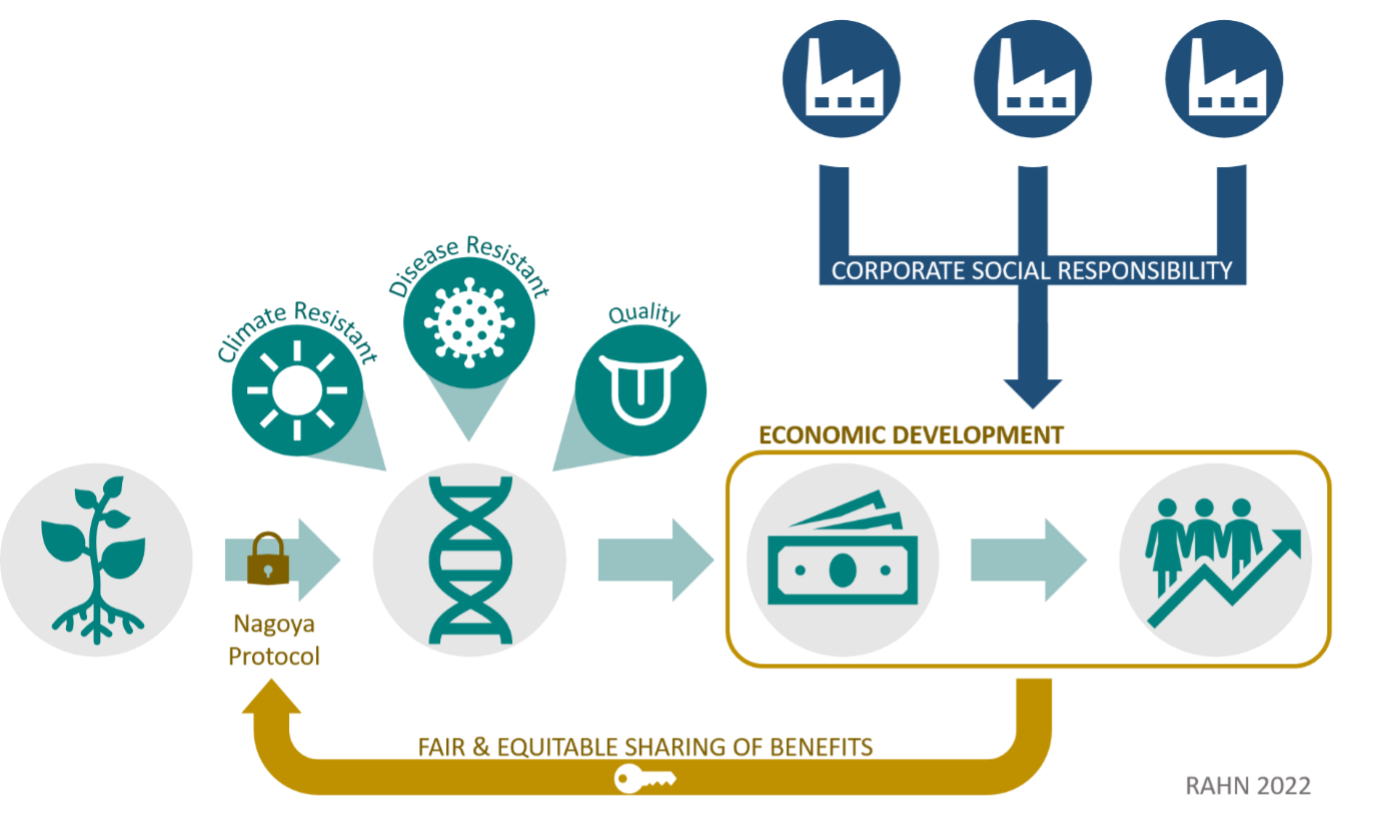

In part one, the importance of innovation and generation of intellectual property (IP) in the context of economic development of corporations and countries was introduced. This was presented as the basis for the green coffee innovation paradox, wherein nations have sovereign rights over their biodiversity, but may not have the resources to transform them into IP to stimulate their economies. Conversely, other countries are well equipped to convert resources into economy-stimulating IP; however, they do not necessarily own the genetic material. To obtain access to foreign genetic resources an agreement must be reached, where necessary, as to how all benefits derived from the research will be shared between nations. Researchers are often unfamiliar with the commercial potential of their work, placing these agreements outside of their realm of expertise and influence. Nevertheless, research conducted without these agreements, when required, is internationally illegal, which is often sufficient to dissuade scientists from engaging in this work.

With the growing need for green coffee research, one is left reflecting on how the economic situation can be rebalanced to resolve the human rights issues. How can we unravel the paradox and liberate access to genetic resources for the purposes of conservation and research?

Figure 1 This schematic attempts to depict the potential value contained within plant genetics and the capacity for their value to drive economic development (green arrows), which is currently restricted by the Nagoya Protocol (pad lock). Nevertheless, industry also drives economic development (blue arrows). Seeing as these pathways are complementary, one may have the potential to unlock the other (gold).

Currently, one gets the distinct impression that the betterment of living standards in the green coffee supply chains are the responsibility of private multinational corporations. The size and affluence of these companies give them vast geographic reach and economic leverage over the practices in their supply chains, presenting them with the opportunity to efficiently implement improvements. Nevertheless, improving human rights, living conditions and agricultural practices will continue to require time (5+ years) and consistent investment, which is unlikely to be associated with a return on investment (ROI) during the shareholder’s tenure at the company.

This reality makes it particularly interesting and relevant to consider how these responsibilities are incorporated into the corporate financial structure. Depending on how these initiatives are integrated, funding will either be considered secure or unsecure. Responsibilities reducing financial risk, either through tax deductions or avoidance of a greater tax penalty, one would anticipate to increase the security of the funding, seeing as it reduces corporate liability. Financing related to asset generation could be considered unsecure if associated with activities meant to maximize the ROIs, such as marketing strategies, since these are vulnerable to corporate decision making. Alternatively, companies may choose to vertically integrate, generating asset value through investment. Vertically integrating into green coffee may be high risk, as ownership of coffee farms will not climate-proof production, potentially leading to depreciation at an accelerated rate over time due to climate change. Nevertheless, it may secure financing for development, as further investment could increase the value of corporate assets.

The omission of purely altruistic motives, in the discussion above, does not mean that these are absent in the business environment, but rather acknowledges that corporations are for-profit organizations that serve the best interests of their shareholders. Shareholder interests are often financial, but not always or exclusively.

Once financing has been secured, corporations must support the right initiatives to ensure timely delivery of an effective solution. Even the best intentions can end up looking superficial, like green washing, if the wrong decisions are made. Seeing as the risks are not confined to the corporations, this endows them with an enormous responsibility to ensure they do not finance initiatives that are either ineffective or intensify problems. Decisions therefore need to be made by those with expertise in these domains, to reduce this risk.

Corporations have accrued expertise in a variety of fields; however, humanitarian, environmental and social responsibility are not necessarily in their repertoire and therefore are likely to be outsourced. Outsourcing creates a marketplace for solutions, which is currently flourishing, however what it does not guarantee is expertise or a solution. The experts needed for these decisions are those who already have decades of experience in these fields before sufficient funding became available. Due to their focus on the domain rather than the funding, these experts generally lack the corporate language of persuasion, marketing. The consequence of this is that those with superior marketing skills receive funding.

Interventions have been sold that leave scientists puzzled as they do not reflect the state of knowledge in that domain and may not even involve leading experts, adding a layer of concern as to what the repercussions of these interventions will be. It might be wise to insure, or start fundraising for future consequences. One may now wish to multiply this concern as companies are conditioned to compete with one another, often resulting in duplication of initiatives, decreasing the efficacy of their actions. Reflecting on whether the intention is to deliver on the sustainability goals, one cannot help but wonder whether there is an alternative, a more effective strategy?

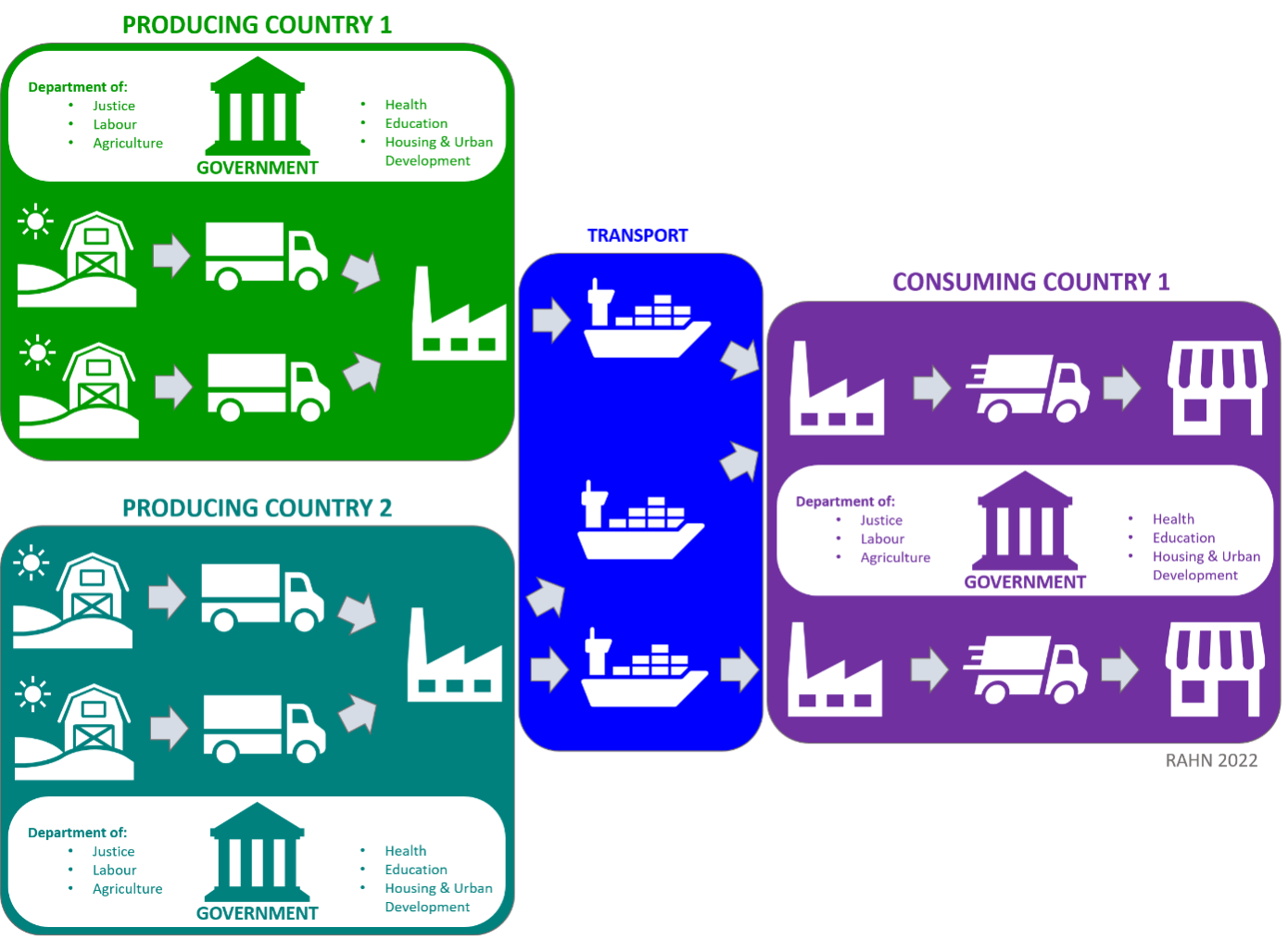

Figure 2 Schematic demonstrating that supply chains cross several national jurisdictions that have their own governing bodies

Companies are linked within any country by their interaction with the national government. Governments theoretically protect the rights of their country, including environment and people. Industries operating within these jurisdictions should comply with these national policies, e.g. environmental and labour standards, if they exist. Therefore, the first question that may arise with the introduction of policies that influence international supply chains, e.g. the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) due diligence directive, is whether there are pre-existing national policies that are not being adhered to, and if not what are the root causes? With the identification of the root causes, multinationals may harmonize their efforts to address these issues by supporting national initiatives. In the absence of harmonization contention may build between corporations and governments as their roles in society become blurred. Regardless, potential points of conflict should be considered risks to effective and efficient implementation and be avoided whenever possible.

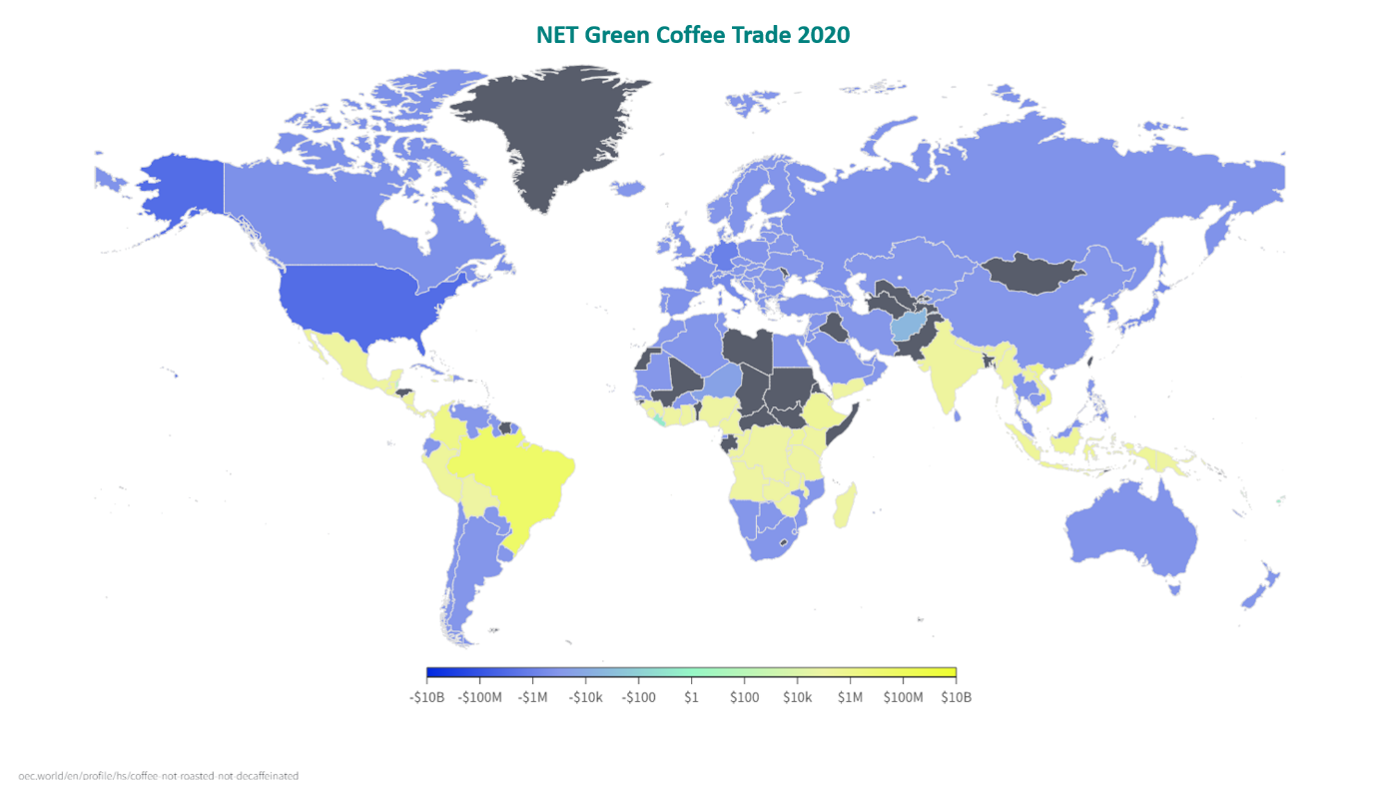

Figure 3 Coffee, not roasted, not caffeinated, 2022

CSR encourages investment in foreign countries through social initiatives, suggesting that modification of the supply chain economics may be a more efficient sustainable solution. Rather than create a feedback loop at the end of the supply chain, reconnecting producing and consuming countries, perhaps modification during the initial interfacing - purchasing of green coffee - would be more efficient? Perhaps it would make sense to introduce a conservation tariff on commodities designed to fund national sustainability projects in producing countries? In essence just rebalancing the corporate books. While I cannot readily capture the complexities of international trade, according to the ICO (2020), “only seven exporting countries continue to apply taxes on coffee exports.” Which if I understood this document properly means that the majority of green coffee exported from producing countries have no tariffs associated with them, suggesting the presence of free trade agreements. This includes all the major producers.

While export tariffs on green coffee have been seen as hindrances to trade and susceptible to distorting the international marketplace, perhaps the current social, agricultural conditions and knowledge deficit are consequences of their absence? When 41.8 million 60kg bags are exported in a three month period (ICO, 2022), introducing a 1% conservation tax on an average price of $1/lb green coffee would result in over $221 million for coffee conservation a year. With the sustained and even increasing demand for green coffee (seen in the current fluctuations in market price), one may argue that green coffee is an inelastic commodity and consequently increasing the price would not diminish market demand.

In a $20 billion USD green coffee market feeding the $200 billion dollar roast coffee market, this proposed level of investment is reasonable and may even be considered modest (ITC, 2021). Not only is this budget approaching the true investment needed in the area, it also distributes the expense according to purchase quantity ensuring that all roasters contribute accordingly. If this cost were to be transferred to the consumers, assuming 400 billion cups of coffee served a year, this would theoretically result in a 0,06 cents/cup increase in price. Furthermore, in theory this would reduce corporate responsibility (and therefore liability) towards conservation and agricultural research while simultaneously stabilizing the funding structure.

Located primarily in producing countries, coffee’s genetic collections and agricultural research centers could be funded by these tariffs. This research in producing countries could help redress the imbalance in value distribution across the supply chain by developing intellectual property. Transparency should be encouraged to ensure funds are properly managed by the national governments. Conservation tariffs could be seen as an investment into sustainable coffee in these economies, indirectly sponsoring education in these domains, construction of infrastructure as well as research, meeting the requirements for fair and equitable sharing of benefits, removing the economic barriers obstructing international collaboration and the sharing of genetic material. Introducing conservation tariffs would also ensure that as long as coffee is traded there will be funding, securing the economic future of green coffee research.

*Author Biography *

Anja Rahn is an award winning researcher with a Ph.D. in Food Chemistry. Specializing in process chemistry, she taught Food Chemistry and Food Analytics at ETH Zurich, before starting her career in coffee as Aroma & Flavour lead at ZHAW's Coffee Excellence Centre.

After becoming an Q & R Grader and leading a number of successful industry projects, she joined JDE-Peet's to lead their Aroma and Flavour research as well as support their sustainability initiatives. Anja is a Senior Scientist at Wageningen Food Safety Research, specializing in Process-Induced Contaminants, she aims to remain an active part of the coffee community.

Please feel free to connect: linkedin.com/in/anjarahn

*References *

Become part of a global community of coffee professionals. Access courses and be the first to hear about news, research and events from across the coffee world.

Join now

© 2024 Coffee Knowledge Hub

Simonelli Group SpA

Via Emilio Betti, 1, 62020

Belforte del Chienti MC

P.IVA 01951160439

VAT n. 01951160439

info@coffeeknowledgehub.com

This website utilises cookies to enable necessary site functionality such as logging you in to your account. By remaining on this website you indicate your consent as outlined in our Cookie Policy.