The first of a three-part series analysing the economics of coffee innovation

Nevertheless, it was not the observation alone that constituted the innovation, as Italian espresso has long been admired by many, but rather the context within which it was interpreted. It is the versatility of thought that contorts and transforms an observation into an innovation. Due to the intellectual nature of this step, innovations are commonly referred to as intellectual property (IP) and are integrated into the “goodwill” component of the corporate valuation, along with their descendants, brands.

Innovations are only truly successful when acknowledged, implemented and adopted by the broader community. When Jean-Paul Gaillard became the Commercial Director of Nespresso in 1988, it is said that Nestle was on the verge of terminating Nespresso. Take a moment to consider this as there are now generations that have never lived in a world without Nespresso. The product launch had been ‘unsuccessful’ according to Mr. Gaillard as the traditional approach of following market research, “cannot work for really new products” (Markides and Oyon, 2000). The decision to pivot Nespresso’s marketing strategy was critical and led to what is called financially a “blockbuster”, increasing the Swiss coffee exports from well below 100 million USD a year in 1991, to over 2 billion USD annually by 2013 and they continue to grow (ICO, 2020).

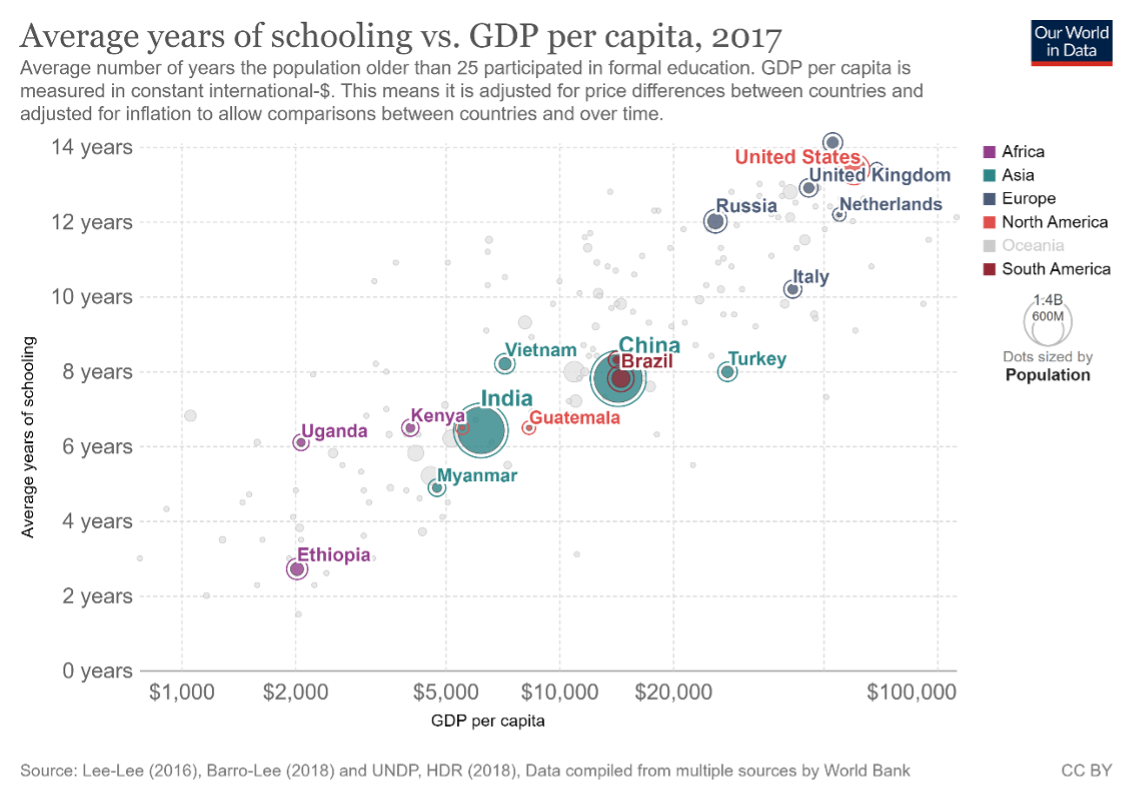

It is the economic potential of innovation that makes research and the generation of IP so valuable. Economists have repeatedly shown that investment in research and development (R&D) is linked to the highest long-term return on investment (ROI), which may be why many governments incentivize investments in this sector. Interestingly, literature also reveals differences in ROI performance in R&D organizations, linking superior performance to organizations that hire highly educated individuals. Also, if you look up national gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and plot it versus the average years of education of a citizen you will observe a similar positive trend.

Coffee consuming countries (developed markets), e.g. Europe, Switzerland and USA, are clustered at one end; highly educated and elevated GDP per capita. Producing and consuming origins (emerging markets), e.g. India, China and Brazil, grouping in the middle, while producing nations (frontier markets), e.g. Ethiopian, Kenya and Uganda, are found at the other extreme. Education should not be considered synonymous with intelligence, but access to knowledge and opportunities.

The prioritization of the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs) have changed the narrative of coffee research, with focus being drawn to agricultural practices and coffee genetics. This area of research remains largely underdeveloped in coffee due to the incredibly high costs and incredibly low ROI (Lambot and Herrera, 2018). The chronic funding deficit has created a paradox where research may add to the economic and human rights rift between developed and developing countries.

The minimal investment in this sector has resulted in coffee origin countries retaining this knowledge. This is an incredibly important point as being the primary knowledge holders of coffee’s agricultural and genetic information gives these countries great economic potential in the current climate change predicament. While many frontier markets (coffee producing countries) lack the resources to harvest their own economic potential, this knowledge can be easily extracted by consuming countries, due to the latter’s level of education, stable infrastructure and world class research facilities. This encourages the export of knowledge as well as the generation of IP abroad, stimulating the economy of an already developed country, rather than the frontier markets of developing countries. As one can readily imagine, this perpetuates the power discrepancy found within the industry and between countries, feeding the accompanying human rights issues. Human rights are interwoven into international policy through the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), as well as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development-Food and Agriculture Organization (OECD-FAO) Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains. The EU has complemented these policies with the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) due diligence directive, further encouraging companies to take responsibility over the practices in their supply chains.

The economic potential of developing countries as well as the power discrepancy was acknowledged by 196 countries when they signed the 1991 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) where an entire objective focuses on, “The fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources” (CBD, 2006). This objective outlines the need to share not only resources and knowledge between countries, but also the resulting benefits. The default system set out in the CBD is that users, including researchers, require Prior Informed Consent (PIC) from the provider country and come to Mutually Agreed Terms (MAT), before the research is commenced, unless the provider country has decided to waive PIC and MAT. This system includes agreeing on the sharing of any potential benefits resulting from the research, which is often outside the researchers’ realm of expertise and influence. For instance Ethiopia estimates their, “wild coffee genetic resources for the world coffee industry in breeding [programs] for disease resistance, low caffeine contents and increased yields is estimated to lie in ranges between 0,5 and 1,5 million USD/year. In the coming 30 years, this value would go up as high as USD 1,45 billion” (Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute, 2015). Fair and equitable sharing of benefits does not necessarily include financial remuneration, but could also encompass activities that encourage economic growth in the providing country, including education and investment in infrastructure.

The people who drive the economic growth, including scientists, are rarely the decision-makers, and consequently being accountable for future economic decisions seems an untenable expectation to have of them. While conducting research and development on genetic resources from certain countries in the absence of PIC and MAT could already be illegal under international law since the coming into force of the CBD in 1993, the law became domestically enforceable with the Nagoya protocol in 2014. This new agreement compels countries where research is conducted to ensure that activities carried out within their territories adhere to the terms agreed upon in the CBD and the accompanying national policy of the provider country of the material. Unable to meet certain legislative obligations, scientists may opt out of this line of research under current regulatory restrictions, in lieu of engaging in illegal activity. Scientists legally and ethically cannot study genetic resources, including green coffee, imported for purposes other than research and development, e.g. food or further processing, without attaining the previously mentioned permissions, if required. Understandably this has significantly stifled research into green coffee genetics, with the exclusion of groups already active in the field, whose rights have been grandfathered in. There are plenty of research groups in developed economies interested in researching coffee genetics, however due to legalities this is currently not possible.

The topic of whether this constitutes unfair competition is a discussion for another time as patenting genetic information is a complex topic and is not entirely restricted, to this author’s knowledge, with several examples already existing in the coffee industry.

With the barrier to progress through bilateral agreements, customary in competitive markets (directly between institutes, though in line with national and international regulations), having been acknowledged, there are now discussions on whether coffee should be included in the multilateral system. Multilateral systems facilitate access to genetic resources through an intermediary, in this case the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Created due to situational urgency posed by climate change, the multilateral system is similarly harmonized with the CBD and known as the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA). Currently, the ITPGRFA includes a list of 64 crops that are a seemingly curious selection, as the list includes strawberries and asparagus yet excludes a number of the major commercial crops, including sugar cane, sugar beets, soybean, oil palm, olives, cocoa and coffee. This gives one the distinct impression that there are far more people who like asparagus than initially thought. Nevertheless, the ITPGRFA focuses on food security and consequently on access to genetic material originating from calorie relevant crops (Flores-Palacios, 2016), which may be needed internationally, for instance in response to severe climate conditions. Although coffee drinkers may argue the necessity of the beverage in their daily lives, unfortunately coffee has a negligible nutritional content unless milk or other condiments are added. While the protection of coffee’s genetic resources are urgently needed they do not fall under the current criteria of the ITPGRFA as coffee’s interdependency is primarily trade and of economic significance rather than nutritional. Furthermore, it should be noted that the vast majority of crops included in the ITPGRFA are annual and likely already comprehensively genetically researched as well as commercially exploited. In the absence of an economic advantage, knowledge can be liberally shared. Economics seems to encapsulate the major concerns surrounding ITPGRFA as it is not domestically enforceable, reverting back to ways of working prior to the Nagoya protocol, with compensation through the “fair and equitable sharing of benefits” fund, with a target budget of 1 billion USD/year, averaging out to 15,6 million USD/crop which once shared globally is minimal. While the current structure of ITPGRFA is attractive for sharing plant genetic resources from a researcher’s perspective, looking at it through the lens of the economic beneficiaries one can understand the reticence of developing countries to participate.

The current situation presents a paradox where prioritization of sustainability initiatives may exacerbate economic and human rights issues, rather than resolve them. In thesecond part of this article we will explore how to unravel this paradox.

Anja Rahn is an award winning researcher with a Ph.D. in Food Chemistry. Specializing in process chemistry, she taught Food Chemistry and Food Analytics at ETH Zurich, before starting her career in coffee as Aroma & Flavour lead at ZHAW's Coffee Excellence Centre.

After becoming an Q & R Grader and leading a number of successful industry projects, she joined JDE-Peet's to lead their Aroma and Flavour research as well as support their sustainability initiatives. Anja is a Senior Scientist at Wageningen Food Safety Research, specializing in Process-Induced Contaminants, she aims to remain an active part of the coffee community.

Please feel free to connect: linkedin.com/in/anjarahn

Favre, Eric (2015) How to turn honey bees into money bees (without being stung). Éditions Favre SA. Lausanne.

Flores-Palacios, X. (2016). Contribution to the Estimation of Countries’ Interdependence in the Area of Plant Genetic Resources. FAO W/W5246/e. DOI:10.13140/RG.2.1.4504.7926

Markides, C. and Oyon, D. (2000). Executive Interview: Changing the Strategy at Nespresso: An Interview with Former CEO Jean-Paul Gaillard. European Management Journal. 18(3): 296-301.

Lambot, Charles and Herrera, Juan Carlos (2018). Disseminating improved coffee varieties for sustainable production. In: Achieving sustainable cultivation of coffee: Breeding and quality traits. Eds Philippe Lashermes. Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing Limited (Cambridge, UK).

CBD (2006) Article 1 Objectives. (Accessed: June 2022). Convention Text (cbd.int)

Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute (2015). Ethiopia’s National Biodiversyty Starategy and Action Plan 2015-2020. CBD Strategy and Action Plan - Ethiopia (English version)

Accedi per lasciare un commento

Become part of a global community of coffee professionals. Access courses and be the first to hear about news, research and events from across the coffee world.

Iscriviti

© 2024 Coffee Knowledge Hub

Simonelli Group SpA

Via Emilio Betti, 1, 62020

Belforte del Chienti MC

P.IVA 01951160439

VAT n. 01951160439

info@coffeeknowledgehub.com

This website utilises cookies to enable necessary site functionality such as logging you in to your account. By remaining on this website you indicate your consent as outlined in our Cookie Policy.